Coastal wetlands such as saltmarshes and mangrove forests provide benefits including storm protection and fisheries support to millions of people around the world. Yet, these habitats are changing rapidly as sea levels rise and temperatures warm, especially in areas affected by both of these stressors at the same time. In the subtropics, for example, saltmarshes are deteriorating from sea level rise while also transitioning to mangrove forests as tropical mangroves trees, migrating further north every year as winters grow milder, replace saltmarsh plants. While maintaining coastal wetland coverage is a growing international priority, we know little about how ecosystems like these, which face multiple stressors, respond to restoration efforts.

One restoration approach gaining popularity today for helping wetlands keep up with sea level rise is thin-layer placement (TLP). This strategy adds thin layers of clean sediment (typically ≤30cm) to the surface of wetlands to rebuild lost elevation. TLP has been successful in northern saltmarshes but remains untested in subtropical regions where different plants, such as mangroves, exist.

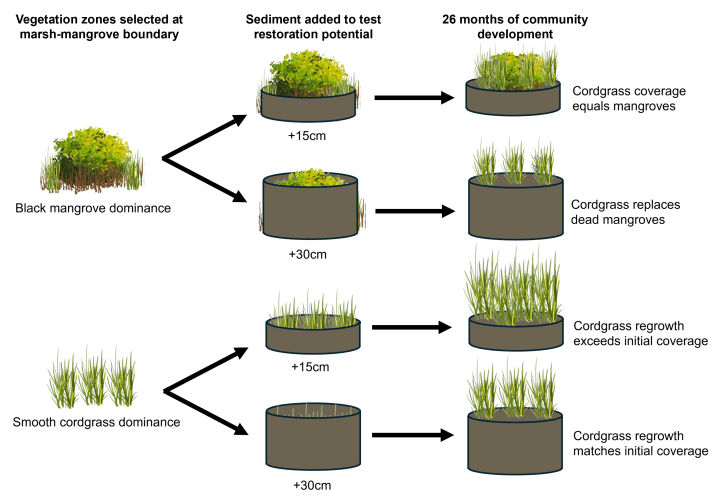

In our study, we explored how a drowning subtropical saltmarsh on the northern Atlantic coast of Florida would respond to TLP restoration. We installed cylinders around individual black mangrove trees and areas of smooth cordgrass, a common saltmarsh grass, and buried plants in different sediment thicknesses (+0cm, +15cm or +30cm) and types (1%-silt or 10%-silt). Over 26 months, we tracked responses to burial.

Buried smooth cordgrass recovered from burial and even benefitted from thinner (+15cm) additions of sediment. In contrast, buried black mangroves declined over time, with smooth cordgrass reclaiming areas where mangrove cover was lost. These outcomes suggest that sediment addition could shift wetlands transitioning to mangrove forest back to saltmarshes. However, we also found that new mangroves (established from seeds) preferred to take root in the higher, drier soils created by sediment addition, indicating that mangrove loss would likely be temporary.

Altogether, our study showed that ecosystems facing multiple pressures can respond to restoration in unique ways. This calls for flexible approaches to managing restored habitats and research in other ecosystems that face similar challenges and are slated for restoration.

This is a Plain Language Summary discussing a recently-published article in Journal of Applied Ecology. Find the full article here.