Understanding the probability of extinction is critical for effective management and conservation. While such assessment mainly depends on rigorous and standardized monitoring (the best of the best data), recent research from Acevedo-Charry et al (2025) features a complementary way that data gathered from volunteers can help estimate probability of extinction.

A version of this post is also available in Spanish here.

How do we assess the probability of extinction during monitoring?

Monitoring is the bread and butter of applied ecology. With monitoring programs, researchers can assess the number of individuals of a species in an area and how those numbers change through time (figure below). Population dynamics can show increasing, decreasing, stable trends between two time points. Simple directional trends, however, can miss critical, more nuanced changes in populations that might provide powerful information about the causes of these population changes.

Instead of using a single trend assessment of the probability of becoming extinct, which could be defined as falling in numbers under a conservation threshold (quasi-extinction), some researchers have proposed to assess this probability simultaneously with the monitoring. With this approach the dynamics of the population are updated and through simulations of near future trajectories, researchers can assess the temporal changes in the probability of (quasi) extinction or its converse, population persistence. The probability of persistence is especially useful when populations move over large areas and therefore, local “extinctions” may simply reflect movement outside the study area.

What did we do?

Standardized monitoring data are often not available locally or globally. The emergence of datasets that leverage observations from multiple volunteers, or community science data, is a promising alternative to assess population dynamics. However, analysing these community science data is challenging, requiring inclusion of different nuanced processes through analytical approaches. To test the performance of a risk-based Viable Population Monitoring framework using volunteer gathered data, we compare estimates of probability of persistence from a standardized monitoring project and the eBird platform.

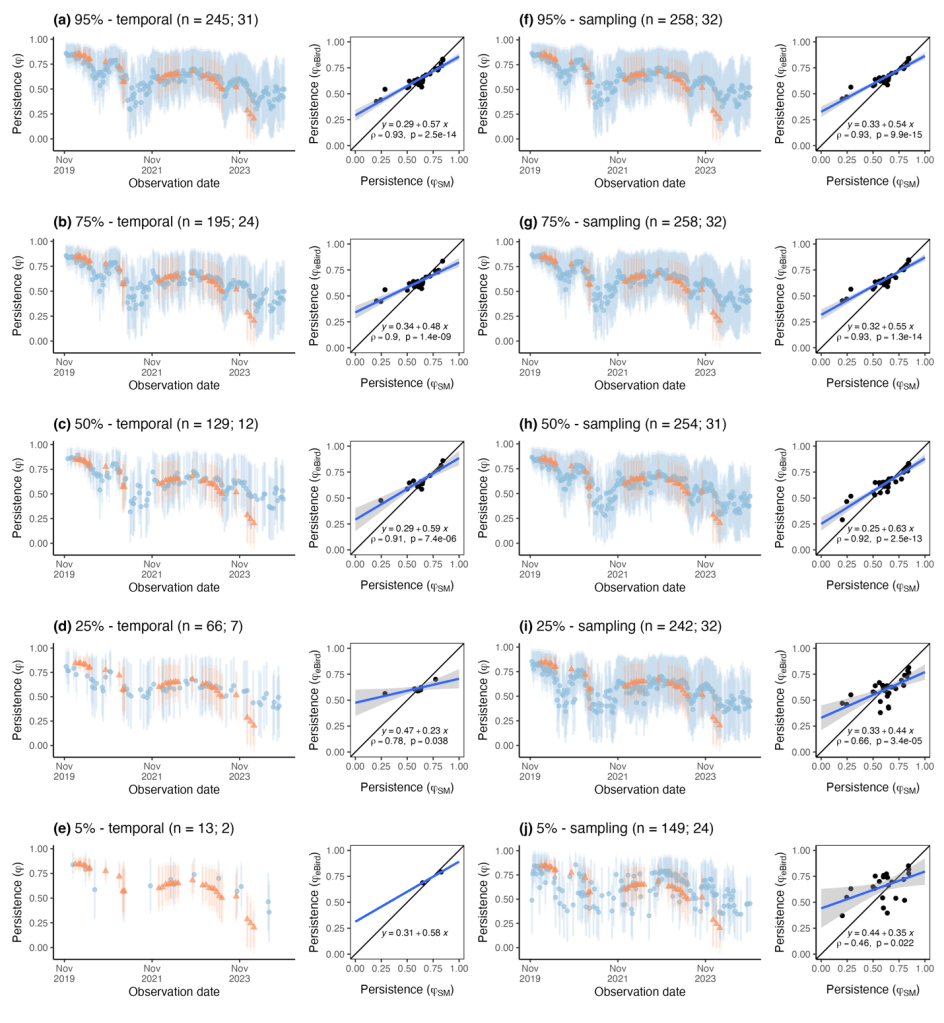

We expected that the data in eBird, a community science platform, would have higher variation in the observation process than the standardized monitoring project that was occurring at the same sites. However, we also tested if the temporal dynamics of counts might reflect the overall dynamic of the population even if not with perfect accuracy. We fitted advanced models to describe the dynamics of the population, using the model parameters estimates to simulate near-future trajectories of the population independently to the two datasets. This approach was conducted iteratively during a 5-year monitoring of the population.

Our results show remarkably similar trends of probability of persistence from the two datasets, even with reduction of eBird data in temporal (weeks) or sampling (lists) scope. By comparing estimates of probability of persistence using eBird and standardized monitoring data, we identify an opportunity to leverage the increasing availability of community science data to monitor population trends and assess extinction risk. Although useful to track population trends and near-term forecasting of population extinction risk, our approach does not replace long-term standardized monitoring projects for population conservation.

What is next?

We love nature. Either by going to the field chasing sounds and colours as birdwatchers, riding an airboat or setting mist nets to mark or count birds, or sitting in front of a computer analysing data, birds motivate in us and many others an infectious enthusiasm to push our knowledge boundaries and understand their lives. Our study species, the snail kite (Rostrhamus sociabilis), is a fascinating example that inspires much collaborative research and applied management, and this approach connects different institutions in the US for its conservation.

We are privileged to be able to monitor snail kites in Florida and foster interdisciplinary collaboration for its conservation. However, many other species’ trends are still undescribed. A crucial aspect of their lives is the risk of extinction, mainly assessed by standardized methods. We do not advocate reducing the effort of conducting rigorous long-term, standardized monitoring. We need these data!! But while other species get the attention of our beloved snail kite, we provide an analytical approach to use community science data to assess their risk of extinction. This is another way to use “the power of the people” to complement our conservation initiatives.

Read the full article ‘Monitoring population extinction risk with community science data’ in Journal of Applied Ecology.