The emergence of citizen science in biodiversity monitoring has transformed the methods by which biodiversity surveys can be conducted. With the recent development of automatic visual identification tools, Pierre Bonnet and colleagues present two distinct case studies implementing citizen science and the use of Pl@ntNet, an automatic plant identification platform.

This article is part of the BES cross-journal special feature on Citizen Science.

Effective monitoring of plant resources is becoming increasingly important for nature reserve management but the challenges in rapidly identifying plant species accurately in the field are myriad, especially for non-specialists. With the development of recent techniques based on automatic visual identification, citizen science initiatives using these techniques can facilitate monitoring by effectively monitoring species change, highlighting presence of rare species and increasing awareness of the threat of invasive species, as well as increasing public awareness and educating all those involved.

Pl@ntNet is an automatic plant identification platform that started in 2009 and the platform is well recognised worldwide in this field. It works on both web and mobile devices with more than 10 million users and a daily usage rate between 250K–500K, with 12% of users utilising the platform in the context of their professional activity.

To understand the strengths and weakness of using such a platform for ecosystem management, we looked at two Pl@ntNet citizen science initiatives used by conservation practitioners in Europe (France) and Africa (Kenya).

The Ramières Reserve, France

The French reserve is characterised by a natural river space of 371 ha, hosting more than 700 plant species located along the Drôme river. Reserve managers used a version of Pl@ntNet dedicated to western European flora which comprehensively covered most flora in France.

Initial identification using the platform was successful, but one of the difficulties of the initiative was finding a way to validate these identifications by involving botanical experts in the species identification validation loop. In response, we developed a new service allowing the experts to download data directly from the web platform to validate the findings, and this feature has now been enabled for all platform users.

The use of the Pl@ntNet platform drastically increased the volume of data produced and shared by the reserve managers. There is still a long way to go before the use of the platform can be included as part of the official reserve management framework, but this initiative clearly opened up the use of citizen science observations to other natural reserve managers around the country.

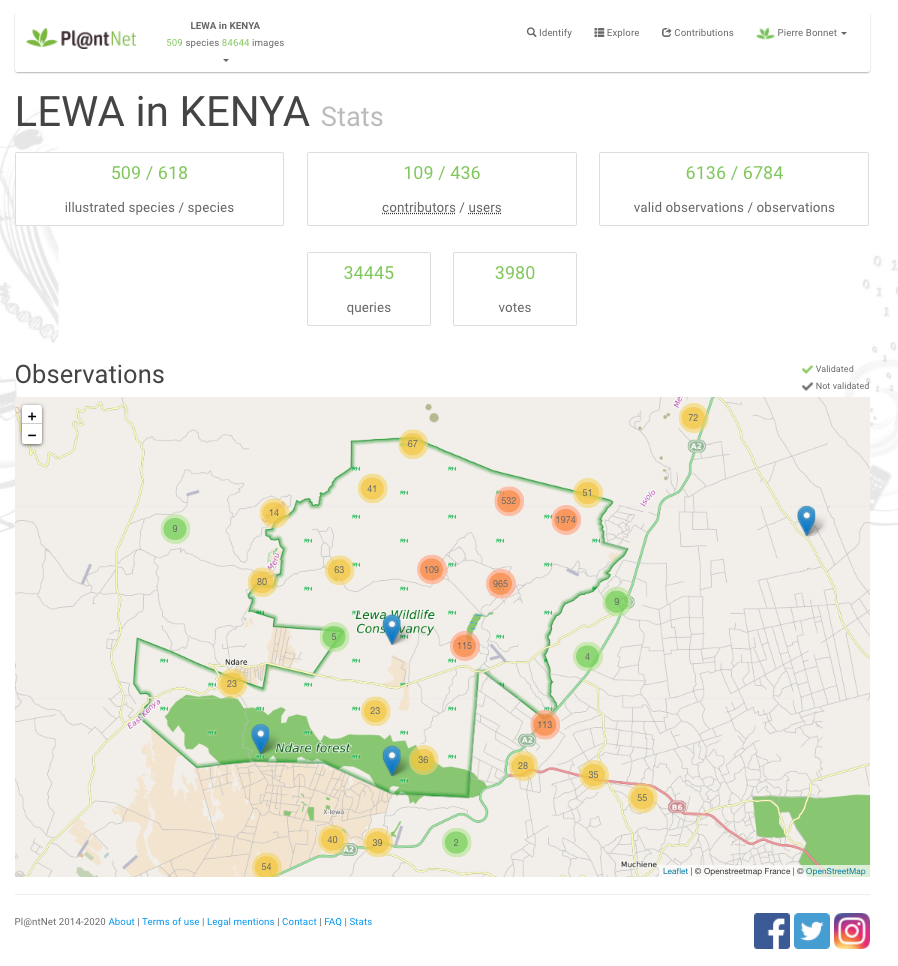

The Lewa Conservancy, Kenya

This Kenyan nature reserve is a UNESCO World Heritage natural site located in the north of Mount Kenya and home to a wide variety of wildlife. The Lewa Conservancy and the Lewa House eco lodge closely collaborated to invest in the customisation of the Pl@ntNet platform to the Lewa flora; restricting the platform to the reserve’s flora can improve identification accuracy and Pl@ntNet users at the Conservancy could access a localised service.

Some of the difficulties faced when implementing this initiative were low internet access in some part of the reserve and the small volume of existing visual data on the reserve’s flora. Rectifying the latter point required strong investment to produce more visual data, especially for the less illustrated species, which enabled species identification performances of the platform to improve through increased usage.

Implementation of this micro-project was fruitful, illustrated by (i) the large volume of new botanical observations produced and shared on the GBIF platform, (ii) the early detection of an invasive species that was not previously recorded, and (iii) the interest of several hundreds of users who experimented the platform since its launch.

Final thoughts

Our study demonstrates how a common citizen science platform can be used and adapted by reserve managers working in very different environmental, sociological and technological contexts to help monitor biodiversity. Although there is still a long way to go, including better engagement of citizen participants in these practices, we hope that this study will encourage others reserves to experiment with such AI-based citizen science platforms in their management processes.

Read the full research: “How citizen scientists contribute to monitor protected areas thanks to automatic plant identification tools” in Issue 1:2 of Ecological Solutions and Evidence.

This article is part of the BES cross-journal special feature on Citizen Science and you can read the full collection here.